Reflections on 2025

The Compute Theory of Everything, grading the homework of a minor deity, and the acoustic preferences of Atlantic salmon

“If an alien intelligence is going to emerge from anywhere...”

Although I am ostensibly tying my shoelaces, I am primarily renegotiating my oxygen debt. My running partner (who is irritatingly aerobic) tilts his head in the direction of Gradient Canopy. The structure cuts a sci-fi silhouette against the night, a cathedral to linear algebra glowing softly in the Mountain View dark. It is a crisp, beautiful evening, marred only by the audible hydraulics of my digestive tract. I am beginning to regret the fifth bottle of Tahoe Artesian Sparkling Water I liberated from the MicroKitchen.

We resume our run.

It is late 2025. The zeitgeist has shifted. In the Permanent Queue for Dishoom (King’s Cross Chapter), “The Wall” is out (again), “Gigawatts” are in (again) and the “DeepSeek Moment” has been usurped by hushed discussions of “Claudiness”. The time has come to reflect on the last twelve months.

And so, adhering strictly to the literary tradition of forcing a complex reality into a three-part listicle, I present my reflections: the Compute Theory of Everything and the sudden traffic jam on the road to Damascus as more holdouts capitulate; the epistemological headache of Scaling Evaluations (or: how to grade the homework of a minor deity); and finally, Floreat Britannia, in which I argue that AI-assisted decision-making might be the only thing capable of saving a nation currently paralysed by the acoustic preferences of Atlantic salmon.

I. The Compute Theory of Everything

I have come to believe that every engineer must walk the road to Damascus in their own time. One does not simply adopt the Compute Theory of Everything by hearing others discuss it. You have to be viscerally shocked by the pyrotechnics of scale in a domain you know too well to be easily impressed.

For many senior engineers, that shock arrived in 2025. I have watched colleagues who were publicly sceptical through 2023 and 2024 quietly start to integrate these systems into their daily work. The “this is just a stochastic parrot” grimace has been replaced by the “this stochastic parrot just fixed my RE2 regex”. They still say “this can’t do what I do”, but the snorts of laughter have been replaced with a thoughtful silence and the subtle refreshing of their LinkedIn profile.

My own conversion came earlier. It is a privilege of my career that I was working in one of the first fields to get unceremoniously steamrollered by scaling: Computer Vision. During a glorious period at the VGG in Oxford, I spent months crafting bespoke, artisanal architectural inductive biases. They were beautiful, clever, and they had good names. And then, in early 2021, my approach was obliterated by a simple system that worked better because it radically scaled up pretraining compute1. I spent a full afternoon walking around University Parks in shock. But by the time I reached the exit, the shock had been replaced by the annoying zeal of a convert.

Returning to my desk, it did not take long to discover that the Compute Theory of Everything is 50 years old and has been waiting patiently in a Stanford filing cabinet since the Ford administration.

In 1976, Hans Moravec wrote an essay called “The Role of Raw Power in Intelligence“, a document that possesses both the punch and the subtlety of a hand grenade. It is the sort of paper that enters the room, clears its throat, and informs the entire field of Artificial Intelligence that their fly is down. Moravec’s central thesis is that intelligence is not a mystical property of symbol manipulation, but a story about processing power, and he would like to explain this to you, at length, using log scales and a tone of suppressed screaming.

He starts with biology, noting that intelligence has evolved somewhat independently in at least four distinct lineages: in cephalopods, in birds, in cetaceans, and in primates. He spends several pages on the brainy octopus covering the independent evolution of copper-based blood and the neural architecture of the arms, citing a documentary in which an octopus figures out how to unscrew a bottle to retrieve a tasty lobster from inside. One gets the impression he prefers the octopus to many of his colleagues. The evolutionary point is that intelligence is not a fragile accident of primate biology. It is a recurring architectural pattern the universe stumbles upon whenever it leaves a pile of neurons unattended. The octopus and the crow did not copy each other’s homework. Instead, they converged on the answer because the answer works. The question is: what is the underlying resource?

Moravec’s answer is: it’s the compute, stupid.

To make his point, he compares the speed of the human optic nerve (approximately ten billion edge-detection operations per second) to the PDP-10 computers then available at Stanford. The gap is a factor of more than a million. He calls this deficit “a major distorting influence in current work, and a reason for disappointing progress.” He accuses the field of wishful thinking, scientific snobbery, and (my favourite) sweeping the compute deficit under the rug “for fear of reduced funding.” It is the sound of a man who has checked the numbers, realized the Emperor has no clothes, and is particularly annoyed that the Emperor has neither a GPU nor a meaningful stake in God’s Chosen Company: Nvidia (GCCN).

This leads to his aviation aphorism that has become modestly famous, at least among the demographic that reads 1976 robotics working papers for recreational purposes: “With enough power, anything will fly.” Before the Wright brothers, serious engineers built ornithopters (machines that flapped their wings, looked elegant, and stayed resolutely on the ground). Most failed. Some fatally. The consensus was that AI was a matter of knowledge representation and symbolic reasoning, and that people who talked about “raw power” were missing the point and possibly also the sort of people who enjoy watching videos of monster truck rallies (a group that includes your humble author). Moravec’s point was that the Symbolic AI crowd were busy building ornithopters, obsessing over lift-to-drag ratios, while the solution was to strap a massive engine to a plank and give researchers the chance to brute-force the laws of physics into submission.

Twenty-two years later, he published an update. “When Will Computer Hardware Match the Human Brain?“ which opens with a sentence that has aged like a 1998 Pomerol:

“The performance of AI machines tends to improve at the same pace that AI researchers get access to faster hardware.”

He plots curves, whips up a Fermi estimate that human-level cognition requires on the order of 100 million MIPS, and predicts this capability will be available in affordable machines by the 2020s. The paper includes a chart in which various organisms and machines are arrayed by estimated computational throughput. The spider outperforms the nematode by a humiliating margin. Deep Blue appears as a reference point for what IBM’s R&D budget bought you in 1997, which was the ability to defeat Garry Kasparov at chess while remaining unable to recognise a photograph of a chess piece. The figure is instructive, but after staring at it for a few minutes, it can start to grate on one’s sensibilities. Perhaps because it treats the human soul as an arithmetic problem. Philosophy on two axes.

The intervening decades are worth examining. From roughly 1960 to 1990, AI researchers were stuck at about 1 MIPS (“barely insect power”). Not because hardware was stagnant (it wasn’t) but because funding structures kept individual research machines small while the number of researchers grew. Moravec calls this period “the big freeze”. Thirty years during which the computing power available to a typical AI researcher was essentially flat. “Entire careers”, he writes, “passed in the frozen winter of 1-MIPS computers, mainly from necessity, but partly from habit and a lingering opinion that the early machines really should have been powerful enough.” But they were not. And rather than updating on this fact, the field developed a lingering resentment toward the hardware, as though the computers were being uncooperative on purpose. The thaw began in the early 1990s and by 1998, individual researchers could access workstations with hundreds of MIPS. “Seeds long ago alleged barren are suddenly sprouting,” Moravec wrote. “Machines read text, recognize speech, even translate languages. Robots drive cross-country, crawl across Mars, and trundle down office corridors.” His conclusion was optimistic, if ominous: “It is still only spring. Wait until summer.”

Summer arrived. It was not a gentle season. The story is by now sufficiently well-rehearsed that I will not recite it in full: deep learning, GPUs, scaling laws, benchmarks falling like dominos at a domino-falling competition, if such competitions exist, and I assume they must, given that our species has managed to turn Microsoft Excel into a televised spectator sport. Rich Sutton’s 2019 essay, “The Bitter Lesson,” stated the principle explicitly. The history of AI, Sutton observed, is the history of methods that leverage computation defeating methods that leverage human knowledge. Search and learning, scaled up, beat hand-engineered cleverness, every time. The lesson is bitter because it means our most sophisticated ideas often fail to compound. Meanwhile, compute does. Researchers who spent years on knowledge representations and expert systems and careful symbolic architectures watched as brute-force gradient descent ate their lunch, then their dinner, then began eyeing their breakfast with intent, asking those researchers if they were sure they were going to finish it. Sutton saw that you should resist the strong urge to build in what you currently know. Build systems that can discover strategies for themselves. Then give them more compute, stand back, and feign the studied indifference of someone who never doubted the thesis.

As a True Believer that The Times They Are a-Changin’, I watch the accelerating obsolescence of my technical skills with mixed emotions. Excitement. Nervousness. Hunger (longer time horizons for coding agents leave ample time to reflect on the question of the lunch menu). We all stand back and witness the repeating signal: quantitative increases in scale producing qualitative shifts in capability. We feed the machine more arithmetic, and it burps out better poetry. Rather than flattening, the curve is compounding.

This brings us back to Moravec’s core insight: “The performance of AI machines tends to improve at the same pace that AI researchers get access to faster hardware.” This is, to me, among the most consequential sentences in the literature. Why? Because the hardware scheduled to come online in the next few years makes the clusters of 2025 look like pocket calculators. I’ve spent many hours this year discussing this with wonderful colleagues (I particularly recommend the inimitable ZD‘s writing on this topic)2. If Moravec is right (and betting against him has historically been a great way to miss the big trends in AI) then we are not approaching a plateau. The octopus is done with the jar. It is now unscrewing the aquarium.

II. Scaling Evaluations

I used to be an assistant professor, a role that is arguably the highest calling of the intellect, provided one enjoys the specific thrill of formatting grant application bibliographies on weekends. One thing you learn while grading scripts at 2am, sustained by lukewarm tea and the sunk cost fallacy, is that writing a rubric is an exercise in hubris. You construct a Platonic ideal of the “correct answer”. Then a student (usually one who treats lecture attendance as a purely theoretical concept) derives the solution using a method revealed to them in a fever dream. The rubric stands revealed as a monument to your own lack of foresight. This is intellectually stimulating in the abstract, but practically disastrous when you have forty papers left to grade and your red pen is running dry. A wrong answer is mercifully quick to process, but a novel right answer is an act of violence. It forces you to halt the assembly line and actually think, a requirement that, at 2am, borders on the unreasonable.

I now work on AI “evals”. The job is effectively the same, except the student has read the entire internet, hallucinates with the confidence of a mid-tier management consultant, and I cannot deduct marks for illegible handwriting. The comfort of my simple handwritten rubrics is behind me. Instead, I find myself staring at a proposed refactor of a distributed training loop, trying to calibrate my skepticism. Is this a brilliant optimization, or a subtle race condition that would only manifest seventy-two hours after deployment, likely on a Sunday evening? On some days, my greatest intellectual contribution is a stubborn refusal to be gaslit by comments like “# after empirical testing, we use LRU to improve caching efficiency”. The author of the comment has performed no such testing, but it knows how to seduce a recovering Carnap fan with the allure of empiricism.

Here is the problem I face, expressed with the brevity that the previous paragraph conspicuously lacked: we are building systems that show early signs of generality, but our evaluation tools must be parochially specific. We are building a universal Swiss Army knife, but we can only test it by asking, “Yes, but can it open this bottle of lukewarm Pinot Grigio?”3

To evaluate poetry you need a poet (or at least a very sensitive undergraduate). To evaluate code you need an engineer capable of reviewing a diff without succumbing to the urge to rewrite it in Rust. To evaluate legal reasoning you need someone who is paid in increments of GDP. The ML literature gleefully tells you that Generality is All You Need. For the evaluation team, however, it means the dreaded ‘examinable content’ now includes, approximately, “everything”. Every gain in generality seeps into some new province of economic activity and we are left measuring the expanding coastline of jagged intelligence with our trusty plastic trundle wheels. No easy feat.

Can we avoid the headache of designing a new syllabus (I would rather eat my red pen) by simply statistically looting the old ones? One project I participated in (in partnership with the skilled data historians at Epoch and the unstoppable Rohin Shah) attempted a purely statistical laundering operation. First, we bravely assumed the existence of something akin to Charles Spearman’s G Factor for AI (not to be confused with Curtis James Jackson III’s G Unit, though both made notable contributions to the psychometrics literature). Then we used the inexhaustible enthusiasm of AI models to answer questions, and have them sit All Of The Exams. Finally, we applied a light dusting of linear algebra via scipy and out came an IQ score. We found the curve has developed a sudden and distinctly vertical aspiration (see here for a nice up-to-date graph).

While we hunted for a raw IQ score, others have taken a temporal approach. Perhaps the most valiant attempt to upgrade our measurement infrastructure in 2025 comes from METR. Their approach wisely declines to define “intelligence” (a trap for the unwary philosopher) and focuses instead on “duration”. Task durations are measured by anchoring to the time taken by skilled humans (see also Ngo’s t-AGI framework). The evaluation probes whether a system can do useful things on a particular distribution of software tasks before it trips over its own shoelaces. In early 2024, the 50% success rate time horizon of the best measured model was roughly 5 minutes. By late 2025, with the release of Claude Opus 4.5, the line sits at 4h49 (though the confidence intervals are currently wide enough to accommodate a fair amount of statistical creative writing).

As the plot has grown in importance and attracted more airtime, there have also been criticisms. Mostly, these don’t target METR (whose epistemological modesty is exemplary) but rather the interpretations the curve has been given online. There are indeed many subtleties and nuances. METR’s HCAST protocol permits internet access, a vital concession to the physiological reality that a software engineer separated from Hacker News for more than 11 minutes enters a state of “computational arrest”. With METR’s curve we are measuring intelligence in chunks of “Late-2024 Humans”, a vintage characterized by high anxiety, low attention span, and a desperate search for relief from Slack notifications4.

One question I have spent time pondering is the following: how can we measure longer horizon tasks, tasks that need teams of humans to complete? How do human teams scale? Of course the relationship is log-linear, otherwise we won’t be able to make nice log plots, but what are the coefficients? How do we assess the impact of the colleague who “replies all” to calendar invites and refuses to use threads in google chat? Will we even be able to measure these teams, now that we have solo engineers with platoons of AI agents dancing across their monitors in a silent ballet of productivity without ever having to endure the awkwardness of a Zoom breakout room. These questions remain excitingly, and socially awkwardly, open.

For many years, the AI field’s Grand Challenge was getting the thing to work at all (specifically, learning to distinguish a handwritten 8 from that curly 3 in MNIST that looks a lot like an 8). We asked, with furrowed brows and chalk on our sleeves, ‘Can we make the sand think?’ That problem is yielding. The sand is thinking. As I write this, the sand is currently refactoring my code and leaving passive-aggressive comments about my variable naming conventions. But the reward for this success is a punishing increase in scope. The surface area of necessary evaluation has exploded from the tidy confines of digit classification to the messy reality of the human condition, the entire global economy and the development of AI itself. We must now accredit a universal polymath on a curriculum that includes everything from international diplomacy to the correct usage of the Oxford comma. There are other Grand Challenges too, such as legibility: ‘What is the sand thinking about, and is it lying?’ Generality means the test syllabus now includes ‘Everything’ and grading the homework of a minor deity requires more than just a bigger TPU cluster and an endless supply of red ink.

And therein lies the allure, dear reader. From where I stand, evaluation science is the place to be in 2026 for those with a high tolerance for ambiguity, a sturdy clipboard and the audacity to ask an AI to fill out its timesheets.

III. Floreat Britannia (in the Era of AI)

May Britain flourish. I mean this unironically.

To say this in late 2025, however, is to mark oneself out as a dangerous contrarian, or perhaps just someone whose internet service provider has been down since the Platinum Jubilee. I say this with the stubborn affection of a developer trying to run Doom on a smart fridge: the hardware is eccentric, the display is glitchy, but deep down, I believe the architecture is solid.

However, to get this fridge rendering smoothly, we need to acknowledge that the operating system (our national capacity for decision-making in this increasingly tenuous metaphor) is currently stuck in a boot loop. My optimism for 2026 is not based on hope (a strategy that historically performs poorly in British weather) but instead on a rather specific mechanism: AI-assisted decision-making.

Britain is not currently flourishing. It is a country that has suffered catastrophic forgetting of its “Industrial Strategy” while overfitting deeply on “Artisanal Sourdough” and “Risk Assessment.” I will now establish this through the standard literary method of listing increasingly dispiriting statistics until the reader either agrees or leaves.

Real wages grew by 33% per decade from 1970 to 2007. Since 2007 they have grown by approximately nothing, representing the longest wage stagnation since the Napoleonic Wars, though in fairness to the current era, Napoleon was eventually defeated and exiled to St Helena, whereas the causes of British wage stagnation remain at large and are frequently invited to speak on panels.

Reviewing the damage, Matt Clifford calculated that if Britain had continued on its pre-2008 growth trajectory, we would now be £16,000 per person per year richer. Median UK earnings sit at £39,000. Median US earnings: $62,000. Adjust for purchasing power and the gap widens further. The UK ranked 27th of 35 OECD nations for wage growth in the 2010s. Since 2019, UK real wages have actually contracted by 0.17% per year, while US real wages grew. I am not aware of a cricketing metaphor that adequately captures seventeen years of follow-on, but I am confident that if one exists, it is unflattering and involves rain.

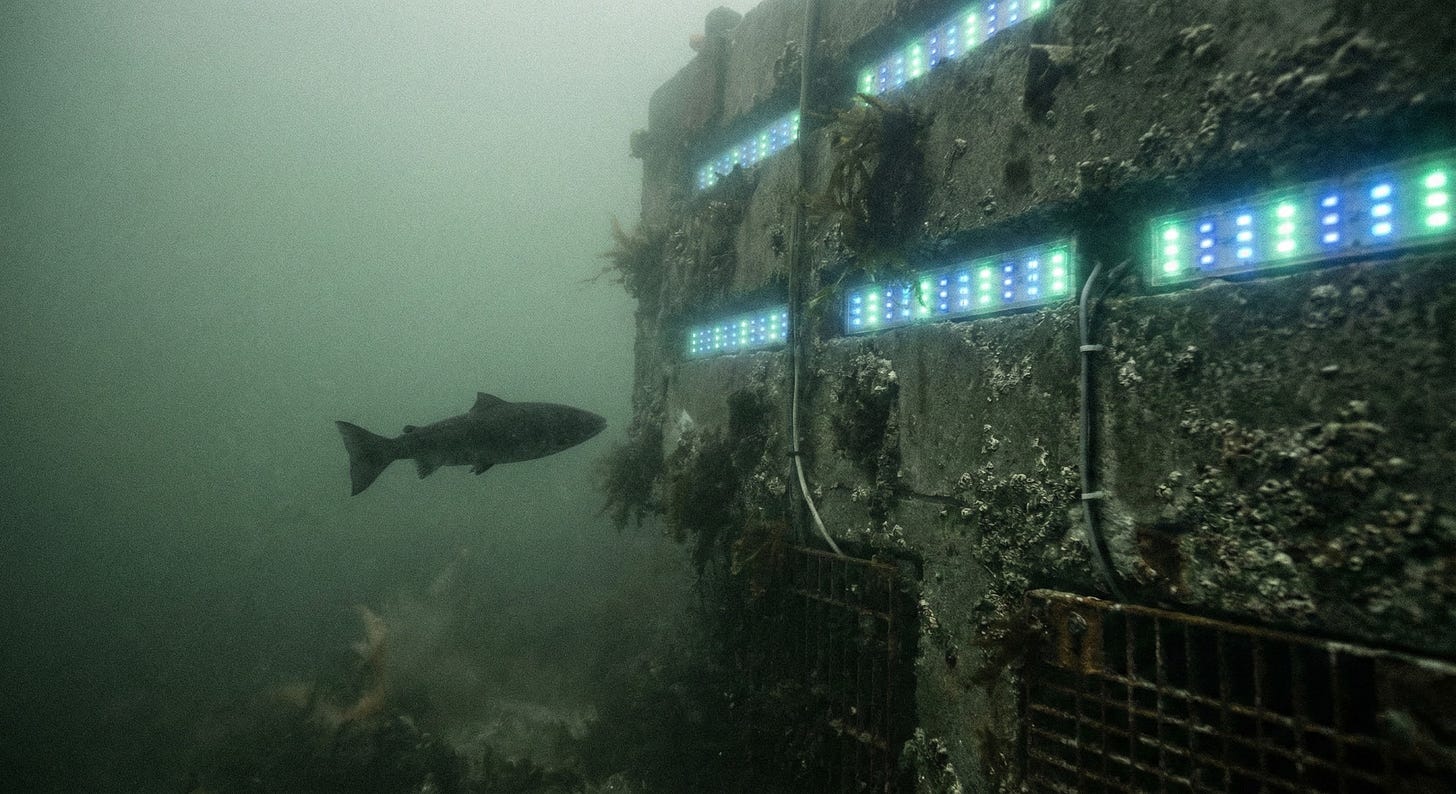

Our industrial electricity prices are the highest in Europe. Hinkley Point C will cost £46 billion, making it the most expensive power station ever built, with a price tag suggesting that the reactor core is being hand-carved by Jony Ive. We’re SotA on cost. South Korea builds equivalent reactors for one-quarter the cost. The Fingleton Report analyses why, citing capital structures and safety frameworks across 162 pages of sober text. But the detail that reached my heart this year, concerns the fish.

Hinkley’s fish protection measures will cost approximately £700 million. This includes an acoustic fish deterrent system referred to, apparently without irony, as the “fish disco”. Based on the developer’s own modelling, this nightclub for aquatic life is expected to save 0.083 Atlantic salmon per year. At £700 million amortised over the system’s life, this values a single salmon at roughly £140 million. This is approximately 700 times the fish’s weight in cocaine5.

The stagnation of British growth is a sunk cost. We cannot unstagnate the 2010s. But what I want, as a citizen, is a system going forward where the primary constraint on energy is not the acoustic preferences of 0.083 salmon.

There are wise souls working on this. I recommend the reliably caustic Alex Chalmers, Sam Bowman’s heroic attempts to enumerate Britain’s challenges, and the non-partisan efforts of the Centre for British Progress. Like these folks, I care deeply about whether Britain flourishes by re-igniting its growth and meaningfully contributing to whatever comes next.

Where I differ is that I am a card-carrying believer in the Compute Theory of Everything.

If Moravec is right, and “The performance of AI machines tends to improve at the same pace that AI researchers get access to faster hardware”, then we are likely to soon see systems that radically reduce the cost of both software and hardware. Given the human creativity and capital it possesses, I think Britain has a fighting shot at gathering the benefits of this transition. The problem is not that we have forgotten how to pour concrete. What we lack is the ability to coordinate resources without forming a committee to investigate the feasibility of a committee.

In future, I expect the bottleneck for our infrastructure projects to shift from engineering to decision-making and coordination. How can we tackle this?

Robin Hanson’s futarchy (policy guided by prediction markets) offers one framework, beloved by the betting nerds, the crypto nerds, and well, basically any of the nerds: bets reveal beliefs, markets aggregate information, decisions improve. The difficulty is that the beliefs being aggregated are themselves unreliable. Forecasting complex systems is genuinely hard. This is less a criticism of Hanson than of the universe, which has shown consistently poor judgment in containing so many interacting variables. Coordinating outcomes that large groups of stakeholders are happy with is hard too, so we have two hard problems.

This makes me profoundly optimistic about the potential impact of AI-assisted decision-making, driven through better AI forecasting6 and AI-enabled coordination. If AI progress continues, the cost of generating high-quality probability estimates is about to be substantially reduced. We can move from a world where rigorous forecasting is a luxury good (available only to hedge funds, meteorologists and Dave who bets on horses) to one where it is broadly accessible. There are major challenges here too (structural risks from correlated predictions etc.), but I’m broadly optimistic.

However, high-fidelity forecasting is useless if your culture treats ‘earnestness’ as a breach of etiquette.

I confess to being an unashamed admirer of the American Spirit. It is, after all, the spirit of a hero of mine, Ben Franklin, a man who looked at a lethal thunderstorm and decided it was the perfect time to fly a kite. It turns out that a nation founded on that sort of practical audacity, alongside ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’, is uniquely calibrated to invent the future. My hope is that Britain stops viewing this instinct as a compliance violation and remembers that we invented the steam engine before we invented the clipboard.

Franklin didn’t confuse audacity with arson. He was a pragmatist who knew that instantaneous combustion tends to hinder one’s long-term career prospects. He respected the raw power of electricity and had the foresight to invent the lightning rod. The Compute Theory of Everything is global, but to prosper we’ll need to build both the kite and the rod. And you cannot catch lightning in a feasibility study. The storm is cresting the horizon, but the spark only favours the nations nervously holding kite strings in the rain. Fortunately, standing in the damp while tinkering with dangerous machinery is practically our national sport. If Britain can get back in the game, I see no reason why the next generation of AI shouldn’t have, at the very least, a dry sense of humour.

Conclusion

We approach the end of the run. The Tahoe Artesian Water has settled into an uneasy truce with my stomach lining and we complete our loop with the cathedral of matrix multiplication in the distance, a glowing testament to American AI ambition, zoning permits and thinking sand. My time in California has come to a close and my flight back across the Atlantic is leaving soon. I am struck by a sense of profound opportunity awaiting in 2026. My only concern is whether I can get this quantity of unbridled optimism through UK Customs without paying a duty (enthusiasm is currently treated as a Class B controlled substance in the Home Counties). Or perhaps it is just the hypoxia.

I was aware of the literature, naturally. But there is a distinction between understanding the mechanics of a steamroller and personally becoming part of the pavement.

I thank ZD for editorial feedback on an initial draft, his valuable technical critiques of the framing and, more broadly, for his unwaveringly interesting conversation. He is the ultimate dinner party guest, possessing the rare ability to make both scaling laws and Isaiah Berlin sound like appropriate conversation for the salad course.

Reflecting on my use of metaphors thus far, I suspect I may have leaned rather too heavily on the grape over the winter break. I shall soldier on, but I shall, mid-essay, take a brief intermission in this footnote to leave an unsolicited link for La Poule Au Pot, another great 2025 discovery for me. Exceptional wine menu. I am told native advertising is the future.

We should probably also remember that our "standard candle" for intelligence spends 40% of its compute cycle checking the price of Bitcoin.

I’m using a 50K GBP per kilo for a 2025 street price estimate, though 40K GBP would also be justified.

Full disclosure: I am an angel investor in Mantic, a London startup building AI-assisted forecasting tools. My investment followed my conviction that AI forecasting is important, not the reverse, but I am not a neutral observer and you should weigh my opinion with whatever skepticism you feel is merited by this information.

This writing is so good it makes me wish I wrote it myself.

great stuff